An interview with Joseph Daher

The rebellion in

Syria has taken the world by surprise and led to the fall of the Assad family

dictatorship, which has ruled Syria since Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, took

power in a coup d’etat 54 years ago. Neither the regime’s military forces nor its

imperial sponsor, Russia, and its regional backer, Iran, were able to defend

it. Cities under the regime’s control have been freed, thousands of political

prisoners liberated from its notorious dungeons, and space opened for a new

fight for a free, inclusive, and democratic Syria for the first time in

decades.

At the same time,

most Syrians know that such a struggle faces enormous challenges, beginning

with the two key rebel forces, Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) and the

Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA). While they spearheaded the military

victory, they are authoritarian and have a history of religious and ethnic

sectarianism. Some on the Left have claimed without foundation that their

rebellion was orchestrated by the U.S. and Israel. Others have uncritically

romanticized these rebel forces as rekindling the original popular revolution

that nearly overthrew Assad’s regime in 2011. Neither captures the complex

dynamics unfolding in Syria today.

In this interview,

conducted amidst a rapidly changing situation in Syria, Tempest asks Swiss

Syrian socialist Joseph Daher about the process that led to

the fall of Assad’s rule, the prospects for progressive forces, and the

challenges they face in fighting for a truly liberated country that serves the

interests of all its peoples and popular classes.

Tempest: How are Syrians feeling

after the fall of the regime?

Joseph Daher: The happiness is unbelievable.

It is a historic day. 54 years of tyranny of Assad’s family is gone. We saw

videos of popular demonstrations throughout the country, from Damascus,

Tartous, Homs, Hama, Aleppo, Qamichli, Suwaida, etc. of all religious sects and

ethnicities, destroying statues and symbols of Assad’s family.

And of course,

there is great happiness for the liberation of political prisoners from the

regime’s prisons, particularly Sednaya prison, known as the “human

slaughterhouse” which could contain 10,000-20,000 prisoners. Some of them had

been detained since the 1980s. Similarly, people, who had been displaced in

2016 or earlier, from Aleppo and other cities, have been able to return to

their homes and neighborhoods, seeing their families for the first time in

years.

At the same time,

in the first days following the military offensive, popular reactions were

initially mixed and confused, reflecting the diversity of political opinion in

Syrian society, both within and outside the country. Some sections were very

happy with the conquest of these territories and the weakening of the regime,

and now its potential fall.

But, some sectors

of the population were, and are still, also fearful of HTS and SNA. They are

worried about the authoritarian and reactionary nature of these forces and

their political project.

And some are

worried about what will happen in the new situation. In particular, wide

sections of Kurds as well as others, while happy for the fall of the

dictatorship of Assad, have issued condemnations of the SNA’s forced

displacement and assassinations of people.

Tempest: Can you recount the sequence

of events, especially the rebel advance, that defeated Assad’s military forces

and led to his downfall? What has happened?

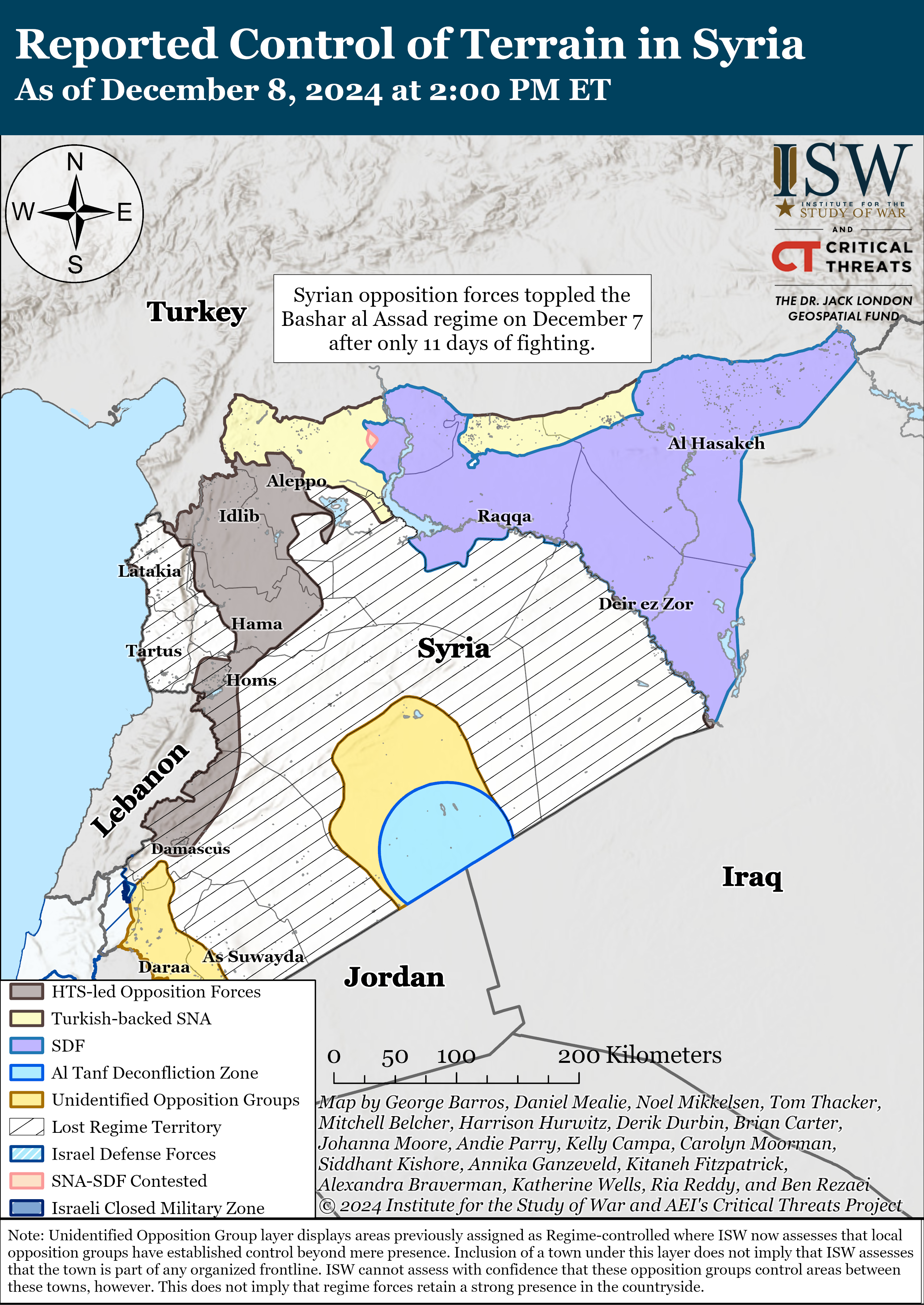

JD: Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) and

Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) launched a military campaign on

November 27, 2024 against the Syrian regime’s forces, scoring stunning

victories. In less than a week, HTS and SNA took control of most of Aleppo and

Idlib governorates. Then, the city Hama, located 210 kilometers north of

Damascus, fell into the hands of HTS and SNA following intense military

confrontations between them and regime forces supported by the Russian air

force. Following Hama, HTS took control of Homs.

Initially, the

Syrian regime sent reinforcements to Hama and Homs, and then, with the support

of the Russian air force, bombed the cities of Idlib and Aleppo and its

surroundings. On December 1 and 2, more than 50 airstrikes hit Idlib, at least

four health facilities, four school facilities, two displacement camps, and a

water station were impacted. The airstrikes have displaced over 48,000 people

and severely disrupted services and aid delivery. The dictator Bashar al-Assad

had promised defeat to his enemies and stated that “terrorism only understands

the discourse of force.” But his regime was already crumbling from everywhere.

While the regime

was losing town after town, the southern governorates of Suweida and Daraa

liberated themselves; their popular and local armed opposition forces, separate

and distinct from HTS and SNA, seized control. Regime forces then withdrew from

localities about ten kilometers from Damascus, and abandoned their positions in

the province of Quneitra, which borders the Golan Heights, which is occupied by

Israel.

As different

opposition armed forces, again not HTS nor SNA, approached the capital

Damascus, regime’s forces just crumbled and withdrew, while demonstrations and

the burning of all symbols of Bashar al-Assad multiplied in the various suburbs

of Damascus. On the night of December 7 and 8, it was announced that Damascus

was liberated. The exact fate and location of Bashar al-Assad was initially

unknown, but some information indicated that he was in Russia under the

protection of Moscow.

The fall of the

regime proved its structural weakness, militarily, economically, and

politically. It collapsed like a house of cards. This is hardly surprising

because it seemed clear that the soldiers were not going to fight for the Assad

regime, given their poor wages and conditions. They preferred to flee or just

not fight rather than defend a regime for which they have very little sympathy,

especially because a lot of them had been forcefully conscripted.

Alongside these

dynamics in the south, others have occurred in different parts of the country

since the start of the rebels’ offensive. First, the SNA led attacks on

territories controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in

northern Aleppo, and then announced the beginning of a new offensive against

the northern city of Manbij, which is under the domination of the SDF. On

Sunday December 8, with the support of the Turkish army, airforce, and

artillery, the SNA entered the city.

Second, the SDF has

captured most of Deir-ez-Zor governorate formerly controlled by Syrian regime

forces and pro-Iran militias, after they had withdrawn to redeploy in other

areas to fight against HTS and SNA. SDF then extended their control over vast

swaths of the northeast previously under the regime’s domination.

Tempest: Who are the rebel forces and

in particular the main rebel formation HTS and SNA? What are their politics,

program, and project? What do the popular classes think of them?

JD: The successful seizure of

Aleppo, Hama, Homs and of other territories in a military campaign led by HTS

reflects in many ways the evolution of this movement over several years into a

more disciplined and more structured organization, both politically and

militarily. It now can produce drones and runs a military academy. HTS has been

able to impose its hegemony on a certain number of military groups, through

both repression and inclusion in the past few years. Based on these

developments, it positioned itself to launch this attack.

It has become a

quasi-state actor in the areas it controls. It has established a government,

the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), which acts as HTS’ civil administration

and provides services. There has been a clear willingness by HTS and SSG in the

past few years to present themselves as a rational force to regional and

international powers in order to normalize its rule. This has notably resulted

in more and more space for some NGOs to operate in key sectors such as

education and healthcare, in which SSG lacks financial resources and expertise.

This does not mean

that no corruption exists in areas under its rule. It has enforced its rule

through authoritarian measures and policing. HTS has notably repressed or

limited activities it considers as contrary to its ideology. For instance, HTS

stopped several projects supporting women, particularly camp residents, under

the pretext that these cultivated ideas of gender equality that were hostile to

its rule. HTS has also targeted and detained political opponents, journalists,

activists, and people it viewed as critics or opponents.

HTS—which is still

categorized as a terrorist organization by many powers including the U.S.—has

also been trying to project a more moderate image of itself, trying to win

recognition that it is now a rational and responsible actor. This evolution

dates back to the rupture of its ties with al-Qaeda in 2016 and its reframing

of its political objectives in the Syrian national framework. It has also

repressed individuals and groups connected to Al-Qaida and the so-called

Islamic State.

In February 2021,

for his first interview with a U.S.journalist, its leader Abu Mohammad

al-Jolani, or Ahmed al-Sharaa (his real name), declared that the region he

controlled “does not represent a threat to the security of Europe and America,”

asserting that areas under its rule would not become a base for operations

abroad.

In this attempt to

define himself as a legitimate interlocutor on the international scene, he

emphasized the group’s role in fighting against terrorism. As part of this

makeover, it has allowed the return of Christians and Druze in some areas and

established contacts with some leaders from these communities.

Following the

capture of Aleppo, HTS continued to present itself as a responsible actor. HTS

fighters for instance immediately posted videos in front of banks, offering

assurances that they wanted to protect private property and assets. They also

promised to protect civilians and minority religious communities, particularly

Christians, because they know that the fate of this community is closely

scrutinized abroad.

Similarly, HTS has

made numerous statements promising similar protection of Kurds and Islamic

minorities such as Ismaelis and Druzes. It also issued a statement regarding

Alawites that called on them to break with the regime, without however

suggesting that HTS would protect them or saying anything clear about their

future. In this statement, HTS describes the Alawite community as an instrument

of the regime against the Syrian people.

Finally, the leader

of HTS, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, has stated that the city of Aleppo will be

managed by a local authority, and all military forces, including those of HTS,

will fully withdraw from the city in the coming weeks. It is clear that

al-Jolani wants to actively engage with local, regional, and international

powers.

However, it is

still an open question as to whether HTS will follow through on these

statements. The organization has been an authoritarian and reactionary

organization with an Islamic fundamentalist ideology, and still has foreign

fighters within its ranks. Many popular demonstrations in the past few years

have occurred in Idlib against its rule and violations of political freedoms

and human rights, including assassinations and torture of opponents.

It is not enough to

tolerate religious or ethnic minorities or allow them to pray. The key issue is

recognizing their rights as equal citizens participating in deciding the future

of the country. More generally, statements by the head of HTS,

al-Jolani, such as “people who fear Islamic governance either have seen

incorrect implementations of it or do not understand it properly,” are

definitely not reassuring, but quite the opposite.

Regarding the

Turkish-backed SNA, it is a coalition of armed groups mostly with Islamic

conservative politics. It has a very bad reputation and is guilty of numerous

human rights violations especially against Kurdish populations in areas under

their control. They have notably participated in the Turkish-led military

campaign to occupy Afrin in 2018, leading to the forced displacement of around

150,000 civilians, the vast majority of them Kurds.

In the current

military campaign, once again SNA serves mainly Turkish objectives in targeting

areas controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Defense Forces (SDF) and with large

Kurdish populations. The SNA has, for instance, captured the city of Tal

Rifaat and Shahba area in northern Aleppo, previously under the governance of

the SDF, leading to the forced displacement of more than 150,000 civilians and many violations of

human rights against Kurdish individuals, including assassinations and

kidnappings. The SNA then announced a military offensive, supported by the

Turkish army on the city of Manbij, home to 100,000 civilians, and controlled

by the SDF.

There are,

therefore, differences between HTS and SNA. The HTS has a relative autonomy

from Turkey in contrast to the SNA, which is controlled by Turkey and serves

its interests. The two forces are different, pursue distinct goals, and have

conflicts between them, although for the moment these have been kept under

wraps. For instance, HTS is currently not seeking to confront the SDF. In

addition to this, the SNA published a critical statement against HTS for their

“aggressive behavior” against SNA members, while HTS reportedly blamed SNA

fighters for looting.

Tempest: For many who have not been

paying attention to Syria, this came out of the blue. What are the roots of

this situation in Syria’s revolution, counter-revolution, and civil war? What

has happened inside the country over the recent period that triggered the

military offensive? What are the regional and international dynamics that

opened space for the rebel advances?

JD: Initially, HTS launched the

military campaign as a reaction to the escalation of attacks and bombing of its

northwestern territory by Assad’s regime and Russia. It also aimed to recapture

areas that the regime had conquered, violating the de-escalation zones agreed

upon in a March 2020 deal, negotiated by Moscow and Tehran. With their

surprising success, however, they expanded their ambitions and openly called

for the overthrow of the regime, which they and others have now accomplished.

The HTS and SNA

have been so successful because of the weakening of the regime’s main allies.

Russia, Assad’s key international sponsor, has diverted its forces and

resources to its imperialist war against Ukraine. As a result, its involvement

in Syria has been significantly more limited than in similar military

operations in previous years.

Its other two key

allies, Lebanon’s Hezbollah and Iran, have been dramatically weakened by Israel

since October 7, 2023. Tel Aviv has carried out assassinations of Hezbollah’s

leadership, including Hassan Nasrallah, decimated its cadre with the pager attacks,

and bombed its forces in Lebanon. Hezbollah is definitely facing its greatest

challenge since its foundation. Israel has also launched waves of strikes

against Iran, exposing its vulnerabilities. It has also increased bombing of

Iranian and Hezbollah positions in Syria in the past few months.

With its main

backers preoccupied and weakened, Assad’s dictatorship was in a vulnerable

position. Because of all its structural weaknesses, lack of support from the

population it rules, unreliability of its own troops, and without international

and regional support, it proved unable to withstand the rebel forces advances

and in city after city and its rule over them has collapsed like a house of

cards.

Tempest: How had the regime’s allies

initially responded? What are their interests in Syria?

JD: Both Russia and Iran initially

pledged to support the regime and also pressured it to fight the HTS and SNA.

In the first days of the offensive, Russia called on the Syrian regime to pull

itself together and “put order in Aleppo,” which seems to indicate that it was

hoping for Damascus to counter-attack.

Iran called for

“coordination” with Moscow in the face of this offensive. It has claimed that

the U.S. and Israel are behind the rebels' offensive against the Syrian

regime’s attempt to destabilize it and divert attention from Israel’s war in

Palestine and Lebanon. Iranian officials declared their full support for the

Syrian regime and confirmed their intentions to maintain and even increase the

presence of their “military advisers” in Syria to support its army. Teheran

also promised to provide missiles and drones to the Syrian regime and even

deploy its own troops.

But this clearly

did not work. Despite Russian bombing of areas outside of the control of the

regime, the rebels’ advance was undeterred.

Both powers have a

lot to lose in Syria. For Iran, Syria is crucial for the transfer of weapons

to, and logistic coordination with, Hezbollah. It was actually rumoured before

the fall of the regime that the Lebanese party has sent a small number of “supervisory

forces” to Homs in order to assist regime’s military forces and 2000 soldiers

in the city of Qusayr, one of its strongholds in Syria near the border with

Lebanon, to defend it in the event of an attack by the rebels. As the regime

was falling, it withdrew its forces.

On its side,

Russia’s Hmeimim airbase in Syria’s Latakia province, and its naval facility at

Tartous on the coast, have been important sites for Russia to assert its

geopolitical clout in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Loss of

these bases would undermine Russia’s status as its intervention in Syria has

been used as an example of how it can use military force to shape events

outside of its borders and compete with western states.

Tempest: What role have other

regional and imperial powers, particularly Turkey, Israel, and the U.S. played

in this scenario? What are their ambitions in the situation?

JD: Despite Turkey’s normalization

with Syria, Ankara has grown frustrated with Damascus. So, it encouraged, or at

least gave the green light to, the military offensive and assisted it one way

or another. Ankara’s objective was initially to improve its position in future

negotiations with the Syrian regime, but also with Iran and Russia.

Now with the fall of the regime, Turkey’s influence is even more important in Syria and probably makes it the key regional actor in the country. Ankara is also seeking to use the SNA to weaken the SDF, which is dominated by the armed wing of the Kurdish party PYD, a sister organization of Turkey’s Kurdish party PKK, which is designated as terrorist by Ankara, the U.S., and the E.U.

Turkey has two

other main objectives. First, they aim to carry out the forced return of Syrian

refugees in Turkey back to Syria. Second, they want to deny Kurdish aspirations

for autonomy and more specifically undermine the Kurdish-led administration in northeast

Syria, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES, also

called Rojava), which would set a precedent for Kurdish self-determination in

Turkey, a threat to the regime as it is currently constituted.

Neither the U.S. nor

Israel had a hand in these events. In fact, the opposite is the case. The U.S.

were worried that the overthrow of the regime could create more instability in

the region. U.S. officials initially declared that the “Assad regime’s ongoing

refusal to engage in the political process outlined in UNSCR 2254, and its

reliance on Russia and Iran, created the conditions now unfolding, including

the collapse of Assad regime lines in northwest Syria.”

It also declared

that it had “nothing to do with this offensive, which is led by Hayat

Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a designated terrorist organization.” Following a visit

to Turkey, Secretary of State Antony Blinken called for de-escalation in Syria.

After the fall of the regime, U.S. officials declared that they will maintain

their presence in eastern Syria, around 900 soldiers, and will take measures

necessary to prevent a resurgence of Islamic State.

For their part,

Israeli officials declared that the “collapse of the Assad

regime would likely create chaos in which military threats against Israel would

develop.” Moreover, Israel has never really supported the overthrow of the

Syrian regime all the way back to the attempted revolution in 2011. In July

2018 Netanyahu did not object to Assad taking back control of the country and

stabilizing his power.

Netanyahu said

Israel would only act against perceived threats, such as Iran and Hezbollah’s

forces and influence, explaining, “We haven’t had a problem with the

Assad regime, for 40 years not a single bullet was fired on the Golan Heights.”

A few hours after the announcement of the fall of the regime, the Israeli

occupation army took control of the Syrian side of Mount Hermon in the Golan

Heights in order to prevent rebels from taking over the area on Sunday.

Earlier, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had ordered the Israeli

occupation army to “take control” of the Golan buffer zone and “adjacent

strategic positions.”

Tempest: Many campists have come to

the defense of Assad yet again, this time contending that a defeat for Assad

would be a setback for the Palestinian liberation struggle. What do you make of

that argument? What will it mean for Palestine?

JD: Yes, campists have argued that

this military offensive is led by “Al-Qaeda and other terrorists” and that it

is a western-imperialist plot against the Syrian regime intended to weaken the

so-called “Axis of Resistance” led by Iran and Hezbollah. Since this Axis

claims to be in support of the Palestinians, the campists claim that the fall

of Assad weakens it and therefore undermines the struggle for the liberation of

Palestine.

Alongside ignoring

any agency to local Syrian actors, the main problem with the argument promoted

by the supporters of the so-called “Axis of Resistance” is their assumption

that the liberation of Palestine will come from above, from these states or

other forces, regardless of their reactionary and authoritarian nature, and

their neoliberal economic policies. That strategy has failed in the past and

will do so again today. In fact, rather than advancing the struggle for the

liberation of Palestine, the Middle East’s authoritarian and despotic states,

whether aligned with the West or opposed to it, have repeatedly betrayed the

Palestinians and even repressed them.

Moreover, the

campists ignore the fact that Iran and Syria’s main objectives are not the

liberation of Palestine but preservation of their states and their economic and

geopolitical interests. They will put those before Palestine every single time.

Syria, in particular, as Netanyahu has made abundantly clear in the quote I

just cited, has not lifted a finger against Israel for decades.

For its part, Iran

has rhetorically supported the Palestinian cause and funded Hamas. But since

October 7, 2023, its main goal has been to improve its standing in the region

so as to be in the best position for future political and economic negotiations

with the U.S. Iran wishes to guarantee its political and security interests and

therefore has been keen to avoid any direct war with Israel.

Its main

geopolitical objective in relation to the Palestinians is not to liberate them,

but to use them as leverage, particularly in its relations with the United

States. Similarly, Iran’s passive response to Israel’s assassination of

Nasrallah, decimation of Hezbollah’s cadres, and its brutal war against Lebanon

demonstrate that its first priority is protecting itself and its interests. It

was not willing to sacrifice these and come to the defense of its key non-state

ally.

Similarly, Iran has

proved itself, as at best, a fickle ally of Hamas. It has reduced its

funding for Hamas when their interests did not coincide. It cut its financial

assistance to Hamas after the Syrian Revolution in 2011, when the Palestinian

movement refused to support the Syrian regime’s murderous repression of Syrian

protesters.

In the case of the

Syrian regime, the argument against their supposed support for Palestine is

airtight. It has not come to the defense of Palestine over the last year of

Israel’s genocidal war. Despite Israel’s bombardment of Syria, before and after

October 7, the regime has not responded. This is in line with the regime’s

policy since 1974 of trying to avoid any significant and direct confrontation

with Israel.

On top of that the

regime has repeatedly repressed Palestinians in Syria, including the killing of

several thousands of them since 2011, laying waste to the Yarmouk refugee camp

in Damascus. They have also attacked the Palestinian national movement

itself. For example, in 1976 Hafez al-Assad, father of his heir and

just-deposed dictator Bashar al-Assad, intervened in Lebanon and supported

far-right Lebanese parties against left-wing Palestinian and Lebanese

organizations.

It also carried out

military operations against Palestinian camps in Beirut in 1985 and 1986. In

1990 approximately 2,500 Palestinian political prisoners were detained in

Syrian prisons.

Given this history,

it is a mistake for the Palestine solidarity movement to defend and align

itself with imperialist or sub-imperialist states that put their

interests before solidarity with Palestine, compete for geopolitical gain, and

exploit their countries’ workers and resources. Of course, U.S. imperialism

remains the region’s main enemy with its exceptional history of war, plunder,

and political domination.

But it makes no

sense to look to reactionary regional powers and other imperialist states like

Russia or China as allies of Palestine or its solidarity movement. There is

simply no evidence to substantiate that position. To choose one imperialism

over another is to guarantee the stability of the capitalist system and the

exploitation of popular classes. Similarly, to support authoritarian and

despotic regimes in pursuit of the objective of liberating Palestine is not

only morally wrong but also has proved itself a failed strategy.

Instead, the

Palestinian solidarity movement must see the liberation of Palestine as bound

up not with the region’s states but with the liberation of its popular classes.

These identify with Palestine and see their own battles for democracy and

equality as intimately tied to the Palestinian struggle for liberation. When

Palestinians fight, it tends to trigger the regional movement for liberation,

and the regional movement feeds back into the one in occupied Palestine.

These struggles are

dialectically connected; they are mutual struggles for collective liberation.

Far-right Israeli minister Avigdor Lieberman recognized the danger that

regional popular uprisings posed to Israel in 2011 when he said that the

Egyptian revolution that toppled Hosni Mubarak and opened the door to a period

of democratic opening in the country was a greater threat to Israel than Iran.

This is not to deny

the right of resistance of Palestinians and Lebanese to Israel’s brutal wars,

but to understand that the united revolt of Palestinian and regional popular

classes alone have the power to transform the entire Middle East and North Africa,

toppling authoritarian regimes, expelling the U.S. and other imperialist

powers. International anti-imperialist solidarity with Palestine and the

region’s popular classes is essential, because they face not just Israel and

the MENA’s reactionary regimes, but also their imperialist backers.

The main task of

the Palestine solidarity movement, particularly in the West, is to denounce the

complicit role of our ruling classes in supporting not only the racist

settler-colonial apartheid state of Israel and its genocidal war against the

Palestinians, but also Israel’s attacks on other countries in the region such

as Lebanon. The movement must pressure those ruling classes to break off any

political, economic, and military relations with Tel Aviv.

In that way, the

solidarity movement can challenge and weaken international and regional support

for Israel, opening the space for Palestinians to free themselves along with

the popular classes in the region.

Tempest: Will the rebels' advance in

Syria open space for progressive forces to renew the revolutionary struggle and

provide an alternative to both the regime and Islamic fundamentalism?

JD: There are no obvious answers

except more questions. Will struggle from below and self-organization be

possible in the areas in which the regime has been expelled? Will civil

society’s organizations (not narrowly defined as NGOs but in a Gramscian sense

of popular mass formations outside of the state) and alternative political

structures with democratic and progressive politics be able to establish

themselves, organize, and constitute a political and social alternative to HTS

and SNA? Will the stretching of HTS and SNA forces allow space to organize

locally?

These are the key

questions, in my opinion, without clear answers. Looking at HTS and SNA’s

policies in the past, they have not encouraged a democratic space to develop,

but quite the opposite. They have been authoritarian. No trust should be

accorded to such forces. Only the self-organization of popular classes fighting

for democratic and progressive demands will create that space and open a path

toward actual liberation. This will depend on overcoming many obstacles from

war fatigue to repression, poverty, and social dislocation.

The main obstacle

has been, is, and will be the authoritarian actors, previously the regime, but

now many of the opposition forces, especially the HTS and SNA; their rule

and the military clashes between them have suffocated the space for democratic

and progressive forces to democratically determine their future. Even in the

spaces freed from regime control we have yet to see popular campaigns of

democratic and progressive resistance. And, where the SNA has conquered Kurdish

areas, it violated Kurds’ rights, repressed them with violence, and forcefully

displaced large numbers of them.

We have to face the

hard fact that there is a glaring absence of an independent democratic and

progressive bloc that is able to organize and clearly oppose the Syrian regime

and Islamic fundamentalist forces. Building this bloc will take time. It will

have to combine struggles against autocracy, exploitation, and all forms of

oppression. It will need to raise demands for democracy, equality, Kurdish

self-determination, and women’s liberation in order to build solidarity among

the country’s exploited and oppressed.

To advance such

demands, that progressive bloc will have to build and rebuild popular

organizations from unions to feminist organizations, community organizations,

and national structures to bring them together. That will require collaboration

between democratic and progressive actors throughout society.

This said, there is

hope, while the key dynamics was initially military and led by HTS and SNA, in

the past few days, we saw growing popular demonstrations and people coming out

in the streets throughout the country. They are not following any orders of HTS,

SNA or any other armed opposition groups. There is a space now, with its

contradictions and challenges as mentioned above, for Syrians to try to rebuild

civilian popular resistance from below and alternative structures of power.

In addition to

this, one of the key tasks will be to tackle the country’s central ethnic

division, the one between Arabs and Kurds. Progressive forces must wage a clear

struggle against Arab chauvinism to overcome this division and forge solidarity

between these populations. This has been a challenge from the start of the

Syrian revolution in 2011 and will have to be confronted and resolved in a

progressive manner in order for the country’s people to be truly liberated.

There is a

desperate need to return to the original aspirations of the Syrian Revolution

for democracy, social justice and equality—and in a fashion that upholds

Kurdish self-determination. While the Kurdish PYD can be criticized for its

mistakes and form of rule, it is not the main obstacle to such solidarity

between Kurds and Arabs. That has been the belligerent and chauvinist positions

and policies of Arab opposition forces in Syria—beginning with the

Arab-dominated Syrian National Coalition followed by the National

Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, the main opposition

bodies in exile supported by the West and regional countries, that tried to

lead the Syrian Revolution in its early years—and today those of the two key

military forces, the HTS and SNA.

In this context,

progressive forces must pursue collaboration between Syrian Arabs and Kurds,

including the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). The AANES project and its political institutions represent

large sections of the Kurdish population and have protected it against various

local and external threats.

That said, it too

has faults and must not be supported uncritically. The PYD and AANES have used

force and repression against political activists and groups challenging its

power. And it has also violated the human rights of civilians. Nonetheless, it

has scored some important achievements, in particular its increase of women’s

participation in all levels in society, as well as the codification of secular

laws and a greater inclusion of religious and ethnic minorities. However, on

socio-economic issues, it has not broken with capitalism and has not adequately

addressed the grievances of the popular classes.

Whatever criticisms

progressives may have of the PYD and the AANES, we must reject and oppose Arab

chauvinist descriptions of it as “the devil” and a “separatist”

ethno-nationalist project. But in rejecting such bigotry, we must not

uncritically romanticize the AANES, as some western anarchists and leftists

have done, misrepresenting it as a new form of democratic power from below.

There has already

been some collaboration between Syrian Arab democrats and progressives and

AANES and institutions connected to it, and that must be built on and expanded.

But, as in any kind of collaboration, this should not be done uncritically.

While it is

important to remind everyone that Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its allies are

the first responsible for the mass killing of hundreds of thousands of

civilians, mass destructions, deepening impoverishment and the current

situation in Syria, the objective of the Syrian revolution goes beyond what HTS

leader, al-Jolani, said in his interview with CNN. It is not only to overthrow

this regime, but to build a society characterized by democracy, equality, and

full rights for oppressed groups. Otherwise, we are only replacing one evil

with another.

Tempest: What impact will the fall of

the regime have on the region and the imperial powers? What position should the

international Left take in this situation?

JD: Following the fall of the

regime, HTS leader al-Jolani stated that Syrian state institutions will be

supervised by the former regime’s Prime Minister Mohammed Jalali until they are

handed over to a new government with full executive powers, following

elections, signalling efforts to secure an orderly transition. Syrian

telecommunications minister Eyad al-Khatib agreed to collaborate with HTS’s

representatives to ensure that telecoms and the internet would continue to

function.

These are clear

indications that HTS wants to carry out a controlled transition of power in

order to appease foreign fears, establish contacts with regional and

international powers, and win recognition as a legitimate force that can be

negotiated with. An obstacle to such normalization is the fact that HTS is

still considered as a terrorist organisation, while Syria is under sanctions.

A period of

instability is nevertheless to be expected in the country. In Damascus, on the

day after the fall of the regime, some chaos in the streets could be seen, the

central bank was for example looted.

It is still hard to

tell what impact the regime’s fall will have on the regional and imperial

powers. For the U.S. and western states, the main objective is now damage

control to prevent chaos extending into the region. Regional states are clearly

not satisfied with the current situation, as they had entered a normalization

process with the regime in the past few years. Regarding Turkey, its main

objective will be to consolidate its power and influence in Syria and get rid

of the Kurdish-led AANES in the northeast. Turkey’s top diplomat actually said

on Sunday that the Turkish state was in contact with rebels in Syria to ensure

that the Islamic State and specifically the “PKK” do not take advantage of the

fall of the Damascus regime to extend their influence.

The different

powers have, however, a common objective: to impose a form of authoritarian

stability in Syria and the region. That, of course, does not mean unity between

the regional and imperial powers. They each have their own, and often

antagonistic, interests, but they do not want the destabilization of the Middle

East and North Africa, especially any kind of instability that would disrupt

the flow of oil to global capitalism.

The international

Left must not side with the remnants of the regime or the local, regional and

international forces of counter-revolution. Instead, the political compass of

revolutionaries should be the principle of solidarity with popular and

progressive struggles from below. This means supporting groups and individuals

organizing and fighting for a progressive and inclusive Syria and building

solidarity between them and the region’s popular classes.

Amidst a volatile

moment in Syria, the Middle East, and North Africa we must avoid the twin traps

of romanticization and defeatism. Instead, we must pursue a strategy of

critical, progressive, international solidarity among popular forces in the

region and throughout the world. This is the Left’s crucial task and

responsibility, especially in these very complex times.

Joseph Daher is a Swiss-Syrian left-wing

activist and scholar. He is author of Hezbollah: The Political Economy

of the Party of God(2016), Syria After the Uprisings: The Political

Economy of State Resilience (2019), and Palestine and Marxism.(2024).