IntroductionAs widely reported, Venezuela is immersed in a major economic, social and political crisis that shows no signs of early resolution.

Among its pressing problems, says Steve Ellner, are “four-digit annual inflation, an appalling deterioration in the standard of living of both popular and middle sectors, and oil industry mismanagement resulting in a decline in production.”

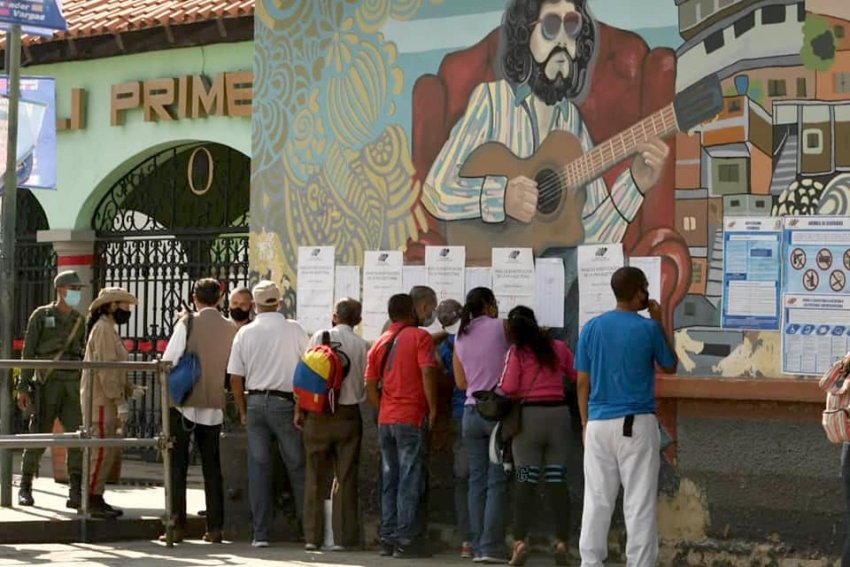

The report by Ellner, a long-time scholar and resident of Venezuela, is highly recommended for its analysis of the economic situation and the constellation of political forces, as well as the limited options facing the government headed by Nicolas Maduro. President Maduro was re-elected May 20 with a 68% majority but 54% of registered voters abstained due to the call for an electoral boycott by the major opposition coalition.

Compounding the country’s many home-grown difficulties, some of which were triggered by the sharp drop in global oil prices of recent years, is the economic war being waged internationally against Venezuela. As Ellner explains, Washington’s hostile actions, which have escalated since Obama incredibly labelled Venezuela an “extraordinary threat to national security” of the USA, “have impacted the Venezuelan economy in many ways.”

The Trudeau government is playing a major role in this offensive against Venezuelan sovereignty, its economy and political leadership. It is participating in the OAS-sponsored Lima Group of right-wing Latin American governments aimed at isolating Venezuela internationally. Immediately following Maduro’s victory in the May 20 election, Ottawa slapped new sanctions on Venezuela, accusing the country’s leaders of murders and other human-rights abuses, and hinting that Canada might ask the International Criminal Court to prosecute Maduro’s government.

Venezuela’s crisis — heavily impacted by the decline in state oil revenues — has led many, including some on the left, to question the resource extraction and export strategies characteristic in varying degrees of all the “progressive” governments elected in Latin America over the last twenty years.

Those strategies have deep roots, however, in the history and social structures of Latin America established by foreign conquest and occupation and as they have evolved in the two centuries since most countries gained their formal independence from their colonial masters.

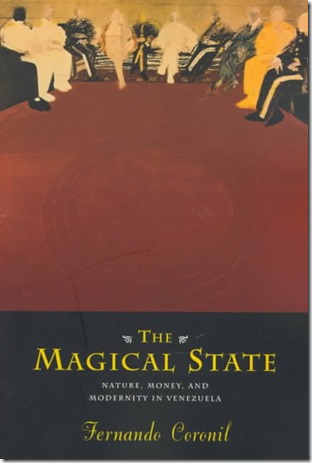

An outstanding analysis of the 20th century background is Fernando Coronil’s book The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela, first published in English in 1997 and later translated into Spanish by a Cuban, Esther Pérez. Coronil (1944-2011) was a Venezuelan anthropologist who spent much of his academic career teaching in the United States.

A classic of Latin American economic and social history, Coronil’s book was published by Nueva Sociedad in 2002, then reissued in 2013 by the publisher Alfa, in Caracas. “One of the fundamental books for understanding Venezuela,” write the editors of Nueva Sociedad in its March-April 2018 edition (No. 274), it “helps us to advance in an analysis of current problems in Venezuela in light of a rentier model that began in the 1930s and has lasted under the Bolivarian Revolution, which today is facing its most critical moment.”

A classic of Latin American economic and social history, Coronil’s book was published by Nueva Sociedad in 2002, then reissued in 2013 by the publisher Alfa, in Caracas. “One of the fundamental books for understanding Venezuela,” write the editors of Nueva Sociedad in its March-April 2018 edition (No. 274), it “helps us to advance in an analysis of current problems in Venezuela in light of a rentier model that began in the 1930s and has lasted under the Bolivarian Revolution, which today is facing its most critical moment.”

Fernando Coronil

The 2013 edition of the book contains a prologue by Venezuelan sociologist Edgardo Lander, reproduced in almost its entirety in Nueva Sociedad. Published below is my translation of Lander’s text. Where Lander quotes Coronil (indented text), I have substituted the English text from his book, with the relevant page references.

Coronil wrote in advance of the recent work by Marxist ecosocialists such as Paul Burkett and John Bellamy Foster on the ecological content in Marx’s work, most of which is still unknown in Latin America. One can only speculate as to how a reading of their studies might have modified his critique of Marx’s alleged failure to incorporate nature in his analysis of the process of wealth creation.

A further caveat for readers in the “Canadian petro-state,” where the Trudeau government is so committed to ecologically disastrous tar-sands extraction and export that it has — contrary to all economic logic — nationalized Kinder Morgan’s Canadian assets to ensure construction of the TransMountain bitumen pipeline expansion to the west coast.

There is a fundamental difference between Venezuela, where rent from oil is the main source of state income, and Canada with its developed manufacturing and service sectors and diversified economy. As Trudeau says, the TransMountain pipeline is an integral part of his government’s Pan-Canadian Framework on fighting climate change — even though the Framework text does not mention pipelines, and his fossil fuels expansion strategy completely belies his claims about Canada’s leading role in fighting climate catastrophe. But mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction account for just over 8% of Canada’s GDP, and energy products (oil, natural gas, etc.) account for about 14% of Canada’s exports. That’s a huge difference from Venezuela, as documented by Lander and Coronil. It’s the difference between a highly developed settler state in the imperial metropolis and a peripheral underdeveloped state in the global South.

– Richard Fidler

* * *

The Magical State is still there

Continuities and ruptures in the history of the Venezuelan petro-state

By Edgardo Lander

Modernity and the neglect of nature and space in social theory

The starting point of Fernando Coronil’s extraordinary study of the historical trajectory of the Venezuelan petro-state, with its ruptures and continuities, is a critique of the hegemonic Eurocentric conception of modernity and its meta-narrative and the analysis of the theoretical and political implications that the exclusion of nature and the priority of time over space have had in the dominant paradigms, both liberal and Marxist.

The author argues that in neither the neoclassical nor Marxist conceptions is nature centrally incorporated as a part of the process of wealth creation, a fact that has huge consequences. In neoclassical theory, the separation of nature from the process of wealth creation is expressed in the subjective market-centered concept of value. From this perspective, the value of any natural resource is determined in the same way as that of any other commodity, that is, by its utility to consumers as it is measured in the market. From a macroeconomic point of view, the remuneration of the owners of land and natural resources is conceived as a transfer of income, not as a payment for a natural capital. This is the conception that serves to support the system of national accounts used throughout the world.

Coronil says that Karl Marx, although he thought the “trinity form” of labor / capital / land “holds in itself all the mysteries of the social production process,” ends by formalizing a conception of wealth formation that occurs inside society as a capital / labor relationship, and leaves out nature. Since value is created in the capital / labor relation and nature does not create value, rent is understood as corresponding to the sphere of distribution, not to the sphere of wealth formation.

According to Coronil, to the extent that nature is left out in the theoretical characterization of the production and development of capitalism and modern society, space is also being left aside from the perspective of theory. By abstracting from nature, from resources, from space and from territories, the historical development of modern society and capitalism appears as an internal process, self-generated by European society, which later expands into “backward” regions. In this Eurocentric construction, colonialism disappears from the field of vision as a constituent dimension of these historical experiences. Accordingly, the presence of the peripheral world and its nature in the constitution of capitalism disappears from view, and the idea of Europe as unique historical subject is reaffirmed.

Once nature is incorporated in social analysis, the organization of work can not be abstracted from its material bases. Consequently, the international division of labor has to be understood not only as a social division of labor, but also as a global division of nature. To break with this set of divisions, particularly those that have been built between material factors and cultural factors, Coronil proposes a holistic perspective of production that includes these orders in the same analytical field. He conceives the productive process simultaneously as creation of commodities and social subjects.

A holistic approach to production encompasses the production of commodities as well as the formation of the social agents involved in this process and therefore unifies within a single analytical field the material and cultural borders within which human beings form themselves as they make their world.... This unifying vision seeks to comprehend the historical constitution of subjects in a world of human-made social relations and understandings. [p. 41]

An appreciation of the role of nature in the formation of wealth offers a different view of capitalism. The inclusion of nature (and of the agents associated with it) should displace the capital/labor relation from the ossified centrality it has been made to occupy by Marxist theory. Together with land, the capital/labor relation may be viewed within a wider process of commodification, the specific form and the effects of which must be demonstrated concretely in each instance. In light of this more comprehensive view of capitalism, it would be difficult to reduce its development to a dialectic of capital and labor originating in advanced centers and expanding to the backward periphery. Instead, the international division of labor could be more properly recognized as being simultaneously an international division of nations and of nature (and of other geopolitical units, such as the first and third worlds, that reflect changing international realignments). By including the worldwide agents involved in the making of capitalism, this perspective makes it possible to envisage a global, non-Eurocentric conception of its development. [p. 61]

In this way, Coronil is theoretically and politically located within the spectrum of critical perspectives of Eurocentric paradigms of modernity and capitalism, diverse perspectives formulated from the experiences of subaltern modernities, that is, from histories and experiences distinct from those of universal history. These histories are those of the majority of the population of the planet, for whom modernity meant colonialism, slavery, extermination, imperial subjection and exploitation.[1]

I argue that this amnesia about nature has entailed forgetting as well the role of the “periphery” in the formation of the modern world, an active “silencing of the past”[2] that reinscribes the violence of a history made at the expense of the labor and the natural resources of peoples relegated to the margins. [pp. 5-6]

The state in the peripheral countries exporting nature

Coronil argues that the exclusion of nature has important consequences for both Marxist and liberal theories of the state.

To the extent that state theories have construed the states of advanced capitalist nations as the general model of the capitalist state, the states of peripheral capitalist societies… are represented as truncated versions of this model; they are identified by a regime of deficits, not by historical differences. But a unifying view of the global formation of states and of capitalism shows that all national states are constituted as mediators of an order that is simultaneously national and international, political and territorial. [p. 65]

This historical difference is a product of the locations that these states have in the international division of labor and of nature. In the process of global accumulation of capital, the main contribution of peripheral countries subjected to colonial relations and imperial control was primarily not the transfer of value but the transfer of wealth, that is, the export of nature. This has enormous consequences for the processes by which states were constituted in these countries. In characterizing the rentier state of peripheral countries whose economy is fundamentally based on the export of nature, we are not simply adding an additional characteristic to the theoretical model of the state: we are talking about a model that, in many ways, differs from what has been theorized as the state in capitalist society.

In metropolitan capitalist countries, states are financed primarily through the withholding of part of the value created by labor subject to capitalist relations (taxes). In this sense, states are dependent on society, on the set of social relations and subjects that operate within it. On the contrary, in the peripheral states exporting nature, the state has as its main source of income the rent of the land. As a landlord, owner of the land and / or subsoil in the name of the nation, the state retains — in the form of rent — part of the wealth extracted from nature. This feature, shared by petro-states with other peripheral countries that are mono-exporters of nature, provides them with a greater degree of autonomy in respect to society, insofar as their income depends less on labor and on the creation of value in their national territory. Incorporating into the analysis the three elements of the wealth creation process (nature, labor, capital) “helps us see the landlord state as an independent economic agent rather than as an exclusively political actor structurally dependent on capital.” This landlord state, even if it is in a subaltern position in the world system, may come to have a greater degree of internal autonomy than what is characteristic of the metropolitan states and may in some way be placed over and above the society.

Constitution of the magical state in Venezuela

Combining, among other factors, the aforementioned theoretical assumptions and the suggestive image formulated by José Ignacio Cabrujas about the state in Venezuela, Coronil formulates the notion of the “magical state” as a perspective from which to unravel to some degree the processes by means of which a state model has been constructed in Venezuela “as a transcendent and unifying agent of the nation.” According to Cabrujas, the appearance of oil in Venezuela creates a kind of cosmogony: the oil wealth had the force of a myth. Thanks to oil it was possible to move quickly from backwardness to a spectacular development. In these conditions, a “providential” state is constituted that “has nothing to do with reality,” but instead emerges from the magician’s hat.[3]

In his journey through twentieth-century Venezuela, Coronil highlights three periods as critical historical milestones in the formation of this magical state and in the process of its constitution as the central location of political power: the dictatorial governments of Generals Juan Vicente Gómez ( 1908-1935) and Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952-1958) and the first government of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-1979). These are three historical periods that correspond to significant increases in oil income. The author states that Venezuelan historiography and the meta-narrative of democratic Venezuela have established an antagonistic rupture between a backward dictatorial country and a democratic and “modern” one. This rupture in the narrative of democracy is used to obscure the extraordinary continuities that have existed in the Venezuelan state since its constitution as a petro-state in the 1930s during the dictatorship of General Gómez until our day.

Coronil believes that “it was during Gómez’s ‘traditional’ regime (...) that it became possible to imagine Venezuela as a modern oil nation, to identify the ruler with the state, and to construe the state as the agent of modernization.” As early as 1928, Venezuela had become the second largest oil producer in the world and the primary exporting country. Thanks to this oil wealth, the Gomecista state managed to appear as the “transcendent and unifying agent of the nation.” With a monopoly not only of violence, but also of the natural wealth of the country, the state appears “as an independent agent capable of imposing its dominion over society.” The foundations of a state and a political system are established in which political confrontations and class struggle would mainly be about access to the state as a primary source of wealth.

After the transition that begins with the death of the dictator in 1935 and the experience of the Acción Democrática (AD) triennium in which “the people” appear as a central reference point, the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship seeks to reconceptualize the relationship between state and people.

The nation’s social body became more marked as the passive beneficiary of its natural body, seen now as the main source of the nation’s powers.... Nature appeared as a social actor not independently but through the mediation of the state. But the military state claimed to represent the nation directly, without the mediation of the people.... This shift marked a subtle but perceptible displacement in the locus of historical agency from the nation’s social body toward its natural body — from the people to nature. [p. 168]

In the New National Ideal of Pérez Jiménez’s government, modernity was understood as “a collection of grand material achievements” that, thanks to the high oil revenues, were used to make large investments in infrastructure, industries and services. Public investment was promoted over private investment, and was especially concentrated in large enterprises like the petrochemical and steel industries (generally associated with the enrichment of senior government officials). The four-fold multiplication of oil prices at the beginning of the first government of Carlos Andrés Pérez laid the foundations for the Greater Venezuela discourse and the popular imagination of a Saudi Venezuela, a land of unlimited abundance, reinforcing the centrality of the rentier petro-state. This imaginary reached its highest expression in the nationalization of the oil industry.

The case studies that are part of the chapters in which the author studies this government illustrate the ways in which this political system operates. Through an approach in which the local conjunctural processes (and the action of the subjects involved in these processes) are interwoven with the tendencies operating in global capitalism, our understanding of both processes is further enhanced. His detailed analysis of the experiences with the tractor factory (Fanatracto) and the automotive policy is extraordinarily illustrative. These studies allow Coronil to unravel the internal operation of the rentier petro-state, in particular the contradictions that are generated within the government with regard to the promotion of industrialization policies and the way in which the contradiction between rentism and value production ends up making these projects fail. A new unfulfilled illusion of the magical state.

The Faustian trade of money for modernity did not bring the capacity to produce but the illusion of production: money brought modern products or factories capable of generating only a truncated modernity. By creating an industrial structure under the protective mantle of petrodollars, the modernization programs of General Marcos Pérez Jiménez and President Carlos Andrés Pérez promoted industries that showed a persistent tendency to function more as traps to capture oil rents then as creative means to produce value. [p. 391]

But the imaginary of the magical state, of the state capable of solving all problems and guaranteeing progress and abundance for all, was broken when the long crisis that had been developing during the governments of Luis Herrera Campins (1979-1984) and Jaime Lusinchi (1984-1989) finally exploded with the Great Turn, the neoliberal adjustment negotiated by Carlos Andrés Pérez with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at the beginning of his second government (1989-1993). The reaction, the Caracazo in February and March 1989, symbolically represented the definitive break between the popular sectors and parties and the state of the Pacto de Punto Fijo.[4]

These events marked a crisis of the populist project that had defined the relationship between state and pueblo since 1936. With the shift to free-market policies and the dismantling of populist developmentalism, dominant discourse began to present the people not so much as the virtuous foundation of democracy, but as an unruly and parasitical mass to be disciplined by the state and made productive by the market. [p. 378]

The living conditions of the popular sectors continued to deteriorate with deepening polarization between an increasingly internationalized privileged elite and an impoverished majority alienated from the political system. In these conditions of a severely divided society (although this division was not recognized by the elites or by the political system), there occurred the attempted coups of 1992, the removal of Carlos Andrés Pérez and, finally, the election of Hugo Chávez Frías as president in December 1998.

The Magical State, Modernity and Nature: current challenges

The Magical state has much to contribute to the debate on the current Venezuelan political process, on central issues such as the state model, the role of oil and the implications of rentier extractivism as a model of society, even if it is called “socialist.” Coronil argues, as indicated above, that in the imaginary of democracy in Venezuela a Manichean view of the primitive and the modern was created, establishing a separation or total rupture between dictatorial regimes and democratic regimes. Similarly, in the current process, the narrative of the revolution and the Fifth Republic is an attempt to define the beginning of a new historical moment in which the continuities that continue to operate despite all the changes that have occurred are completely erased from the collective consciousness. This silence has to do fundamentally with the state model, the relations between society and the rentier petro-state, and with the specific modalities of this society’s relationship with its natural environment, with oil. It is a silence that, insofar as it is installed in the collective consciousness because we are said to be in another historical time, the Bolivarian Revolution, which has nothing to do with the past, denies us the very possibility of understanding what is happening in the country, as well as the possibility of imagining future alternatives to this petro-state model of society.

The certification of the hydrocarbon reserves of the Orinoco Oil Belt as the largest in the world has given a new and vigorous impulse to the idea that oil will guarantee a future of progress, prosperity and abundance. The imaginary of Greater Venezuela is now replaced by that of Venezuela as the Gran Poder Petrolera, the Great Oil Power. The idea of ”sowing the oil,” traditionally understood as the unrealized ideal of using the resources from the oil rent for the development of other productive activities, is altered and converted into the use of that income to make the massive investments required to increase production and increase dependence on oil production and export. Between 2010 and 2012, oil represented 95% or 96% of the total value of the country’s exports, together with a significant reduction in non-oil exports in both absolute and relative terms. In 1998, non-oil exports amounted to $5.529 billion; by 2011, these had fallen to $4.679 billion. In the intervening years, private exports, almost exclusively non-oil, were reduced by half (they went from $4.162 billion in 1998 to $2.131 billion in 2011). In the same period, the participation of the industrial sector in GDP fell from 17.4% to 14.5%.[5]

After 14 years of the Bolivarian Revolution, Venezuela is more rentier than ever. The state has regained its place at the center of the national scene. With its oil income — according to the official discourse — it will once again have the capacity to lead Venezuelan society towards progress and abundance. A new and essential component is now added to these already traditional relations between petro-state and society. In the absence of a critical debate on the experience of 20th century socialism, “21st century socialism” is declared to be the goal of the Bolivarian process, and the need for a single party of the revolution is postulated. Despite what the Constitution says, the tendency is to associate socialism with more state. The nationalized companies come to be called, by that fact alone, “socialist companies.” The petro-state thus becomes the vanguard that directs social transformation and its strengthening becomes an expression of the progress of the “transition towards socialism.” Unlike the socialist experiences of the last century, a new type of relationship between state and party is established. Instead of a revolutionary party that controls the state, the petro-state has been used to create, finance and lead the party. As a model, there is still a predominance of a raison d’état in that the state is identified with the nation, with the people and with the common good, and is therefore the place in which all the initiatives and main decisions must necessarily be concentrated. This discards, denies, mutilates, the only way through which the democratic transformation of society is possible: broad, varied, multiple processes of autonomous social experimentation that emerge from the diversity of practices, memories and projects of the various peoples, social sectors, regions and cultures of the country.

The Great National Petroleum Consensus of the nation’s quasi-ontological identification with oil was again sealed with the 2012 presidential elections. Despite the profound contrasts on practically all other issues related to the model of the country proposed in the electoral campaign programs, government and opposition alike coincide on one point: the proposal to double oil production to take it to six million barrels per day by the end of the presidential period 2013-2019.[6]

There have been repeated references by Chávez and in the public policy documents of these years to the need to get out of the rentier and monoproductive oil logic. These are reiterated in the election program presented by Chávez in the presidential elections of October 2012, which states: “Let us not be deceived: the socio-economic formation that still prevails in Venezuela is capitalist and rentier.”[7] Consequently, the need is formulated: “To promote the transformation of the economic system, based on the transition to Bolivarian socialism, going beyond the capitalist oil rentier model towards the productive socialist economic model based on the development of the productive forces.”[8]

Likewise, in recognition of the severity of the global environmental crisis, one of the five Great Historical Objectives formulated in this plan is to “preserve life on the planet and preserve the human species.” This is specified in the following terms:

Build and promote the eco-socialist productive economic model, based on a harmonious relationship between man and nature, which guarantees the rational, optimal and sustainable use and exploitation of natural resources, respecting the processes and cycles of nature. Protect and defend the permanent sovereignty of the state over natural resources for the supreme benefit of our people, who will be its principal guarantor. Contribute to the formation of a great global movement to contain the causes and repair the effects of climate change that occur as a consequence of the predatory capitalist model.[9]

However, and very contradictorily, another of the major objectives of the plan is “to consolidate the role of Venezuela as a world energy power.”[10] To that end, as already mentioned, the plan proposes to double the level of oil production, especially by expanding production in the Orinoco Belt, to take it to 4 million barrels a day, and a huge expansion in gas exploitation to reach 11.947 billion cubic feet per day by 2019.

With this extraordinary expansion, which requires very high amounts of investment and technologies that the country does not have, Venezuela’s dependence on oil is increased in the long term and the participation of transnational, public and private oil corporations in the Venezuelan oil business is expanded. In many of the contracts through which massive credits were obtained by China it is established that they will be paid with oil. This means that just to maintain the current levels of fiscal revenues in the future, the Venezuelan state would have little latitude and would be committed in the long term to increase production and export levels of crude oil.

From the standpoint of the socio-environmental impact, the consequences of this leap in production levels would certainly be much more severe than the devastating effects of a century of oil production in the country, especially in Lake Maracaibo — the largest in Latin America — which has been converted by both transnational corporations and the state-owned oil company into an “area of sacrifice” in some of the largest “collateral” environmental damage in oil production on the entire planet. The deposits of the Orinoco Belt are made up of heavy and extra-heavy oils and hydrocarbon sands whose exploitation requires huge volumes of water and generates much more toxic waste than the exploitation of lighter petroleum. The country (as well as the continent and planet) run the risk that the extraordinary river system of the Orinoco and its delta will suffer the same consequences as Lake Maracaibo.

Thus this political project can not be detached from the logic of the rentier petro-state and the recycled imaginary of Greater Venezuela, nor is this even conceivable. What is revolutionary in this program is not to alter the relationship of Venezuelan society with oil, or to suggest some other way to understand the relationship of society with nature. No, what is revolutionary is to deepen the rentier logic and the role of the state in its function as a great decision-maker and redistributor of the rent. In this government program what defines the revolutionary character of petroleum policy is gauged by three criteria: the state captures the rent, the value obtained from this income is maximized and these revenues are used for the benefit of the people.

Finally, our oil policy must be revolutionary, which has to do with who captures the oil rent, how it is captured and how it is distributed. According to this vision, there is no doubt that the state should control and capture the oil rent, based on mechanisms that maximize its value, in order to distribute it for the benefit of the people, seeking the integral social development of the country, in more just and equitable conditions. This is the element [so the argument goes] that would differentiate us from any other oil policy.[11]

The imaginary of progress, of the role of oil as the lever that will guarantee the modernization of the country under the direction of the state, has an extraordinary continuity here. The following text by Carlos Andrés Pérez as he nationalized the oil industry could easily be confused as an expression of the common sense of the Bolivarian imaginary of this new illusion of Venezuela as a great power:

Venezuelan oil must become an instrument of Latin American integration and a source of global security, human progress, international justice, and balanced economic interdependence. It also must become a symbol of Venezuela’s independence, its national will, and its creative capacity as a people and a nation. Venezuelan petroleum is an encounter with our destiny. There is no better place to express it than in the presence of Simón Bolívar, who taught us to believe in our people and knew how to fight to show what we are capable of achieving.[12]

The confluence of the logic of the magical state with the Leninist logic of statism and vanguardism and the charismatic / messianic style of Chávez’s leadership contradicts, and again and again blocks the advance of the very widespread processes of participation and autonomous organization of the popular sectors. The dependence on the “downloading” of state resources for community projects is systematic. A political culture is installed of a cult to the “comandante-presidente,” to “our leader,” and there are constant references to something being done because “Chávez commanded” or issued “orders that have to be obeyed.” It has been publicly stated that the decision to define the Bolivarian process as socialist was made by Chávez alone. And all this can only undermine the construction of a democratic culture, insofar as that involves building collective consciousness, because no matter how much social organization is built, all the most important decisions are taken elsewhere.

On the basis of the same relationship with nature and the same model of a rentier petro-state, it is not possible to produce significant transformations in Venezuelan society. It is possible to create a model of state capitalism in which the rent is better distributed and is directed primarily to the previously excluded social sectors. Higher levels of equity and reduction of exclusion can be achieved, but it cannot generate the political-organizational and productive capacity of the whole society that is required for its transformation. In this way, nature will continue to be devastated and the possibility of making a reality the pluricultural republic of which the Constitution speaks will be denied.

[1] Among the more important contributions to these radical critiques of Eurocentrism are the production of the Subaltern Studies Group of India, the contribution of African theorists such as V.Y. Mudimbe and the influential texts of Edward Said and Martín Bernal. In the Latin American context, Coronil actively participated in the collective construction of the modernity / coloniality perspective, among which outstanding figures are Aníbal Quijano, Enrique Dussel, Arturo Escobar and Walter Mignolo.

[2] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, 1995.

[3] One of the greatest riches of the book is the way in which it processes the dialogue between the theoretical-conceptual production of the academic disciplines of social sciences and literary production, the plastic arts and Latin American popular music. The analysis is further enriched with references to authors and works that are not part of the canon of social sciences and that have the virtue of looking at things from another place, from other perspectives, from other sensibilities: Jacobo Borges, José Ignacio Cabrujas, Rómulo Gallegos, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez, Alejo Carpentier, among others.

[4] Political agreement to guarantee the transition after the fall of Pérez Jiménez, who enabled a bipartisan system formed by AD and the Committee of Independent Electoral Political Organization (known by its acronym COPEI). The Communist Party was excluded from this pact. [Nueva Sociedad editor’s note]

[5] Banco Central de Venezuela, “Información estadistica. Exportaciones e importaciones de bienes y servicios,” http://200.74.197.135/c2/indicadores.asp.

[6] The proposal of Henrique Capriles Radonski can be found in “Hay un camino. Petróleo para tu progreso,” <https://henriquecapriles.wordpress.com/2012/08/05/petroleo-para-el-progreso/>.

Hugo Chávez’s election program is at “Propuesta del candidato de la Patria comandante Hugo Chávez para la gestión bolivariana socialista 2013-2019,” Caracas, 11/6/2012, <www.mppeuct.gob.ve/sites/default/files/descargables/programa-patria-2013-2019.pdf>.

[7] “Propuesta del candidato de la Patria comandante Hugo Chávez para la gestión bolivariana socialista 2013-2019,” supra, note 6.

[8] Ibid., p. 9

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Op. cit., p. 12.

[12] Carlos Andrés Pérez, “Speech on the Law for Nationalization of Oil,” 29 August 1975, https://tinyurl.com/ycobt4jg.