“The climate crisis cannot be solved within capitalism, and the sooner we face up to this fact the better.” – Jason Hickel.

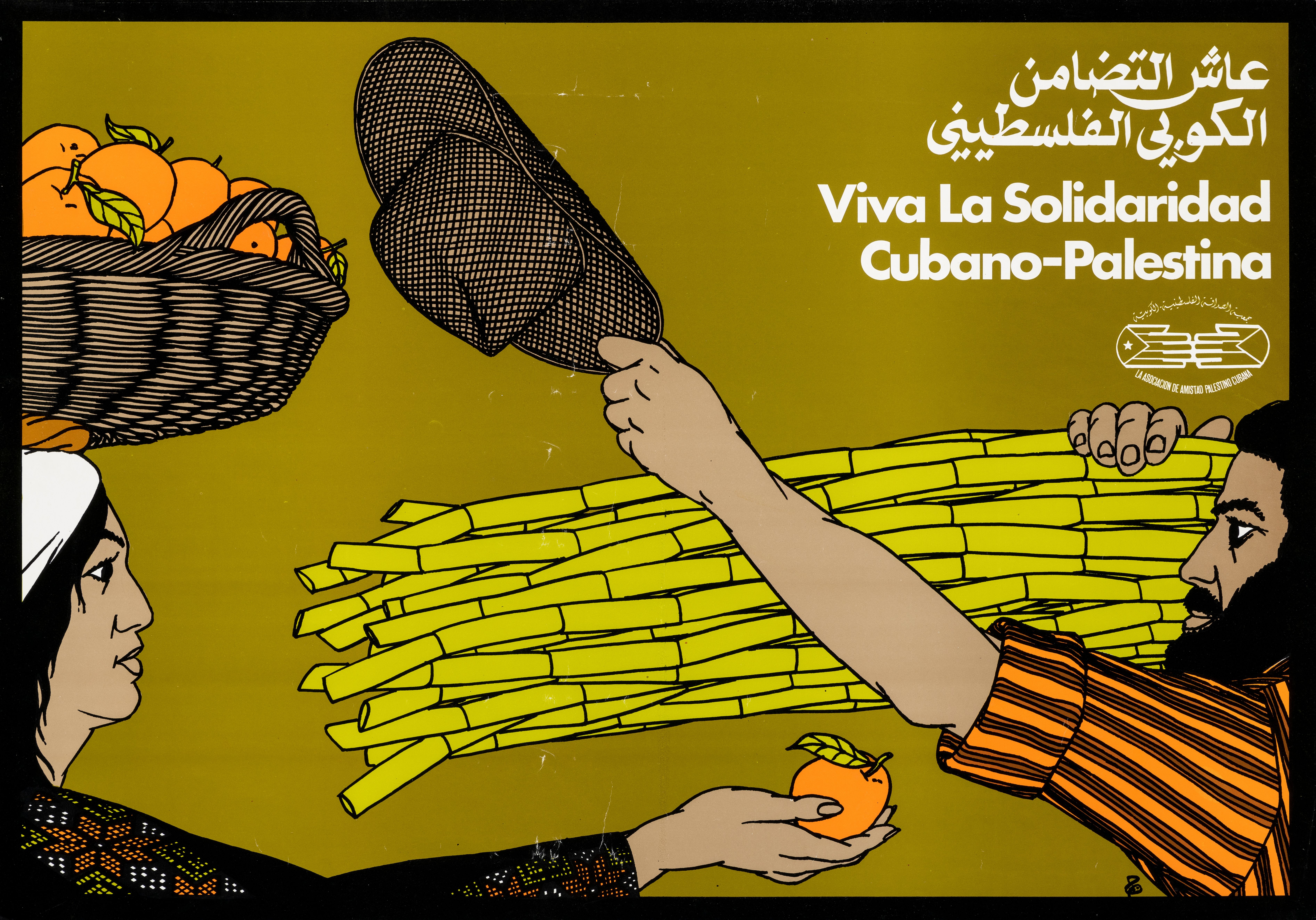

Viva La Solidaridad Cubano-Palestina is emblematic of Cuba’s longstanding solidarity with Palestine – which predates this poster made by Marc Rudin in 1989 and still stands today.

Meeting in Havana, Cuba on April 28 to May 1, leading scholars, diplomats and policy-makers from 36 countries mapped plans to present a program of action for establishment of a New International Economic Order that will be presented to the September meeting of the United Nations General Assembly.

The Havana conference – co-convened by the Progressive International and the Asociación Nacional de Economistas y Contadores de Cuba – marked the 50th anniversary of an earlier version of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), a set of proposals to end economic colonialism and dependency adopted by the UN on May 1, 1974.

A keynote speaker at the Havana conference was Jason Hickel. He teaches at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA-UAB) in Barcelona and is a visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics. Hickel is best-known, perhaps for his book Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (2020), which presents degrowth as an anticapitalist alternative to ecological imperialism and unequal exchange.

I will say more about the Havana congress following Hickel’s address, which I thank the Progressive International for making available. – Richard Fidler

* * *

Climate, Energy and Natural Resources

By Jason Hickel

Thank you to Progressive International for organizing this event, and thank you to our Cuban hosts, who have kept this revolution alive against extraordinary odds. The US blockade against Cuba, like the genocide in Gaza, is a constant reminder of the egregious violence of the imperialist world order and why we must overcome it.

So too is the ecological crisis. Comrades, I do not need to tell you about the severity of the situation we are in. It stares every sane observer in the face. But the dominant analysis of this crisis and what to do about it is woefully inadequate. We call it the Anthropocene, but we must be clear: it is not humans as such that are causing this crisis. Ecological breakdown is being driven by the capitalist economic system, and – like capitalism itself – is strongly characterized by colonial dynamics.

This is clear when it comes to climate change. The countries of the global North are responsible for around 90% of all cumulative emissions in excess of the safe planetary boundary – in other words, the emissions that are driving climate breakdown. By contrast the global South, by which I mean all of Asia, Africa and Latin America, are together responsible for only about 10%, and in fact most global South countries remain within their fair shares of the planetary boundary and have therefore not contributed to the crisis at all.

And yet, the overwhelming majority of the impacts of climate breakdown are set to affect the territories of the global South, and indeed this is already happening. The South suffers 80-90% of the economic costs and damages inflicted by climate breakdown, and around 99% of all climate-related deaths. It would be difficult to overstate the scale of this injustice. With present policy, we are headed for around 3 degrees of global warming. At this level some 2 billion people across the tropics will be exposed to extreme heat and substantially increased mortality risk; droughts will destabilize agricultural systems and lead to multi-breadbasket failures; and hundreds of millions of people will be displaced from their homes.

Climate breakdown is a process of atmospheric colonization. The atmosphere is a shared commons, on which all of us depend for our existence, and the core economies have appropriated it for their own enrichment, with devastating consequences for all of life on Earth, which are playing out along colonial lines. For the global South in particular, this crisis is existential and it must be stopped.

But so far our ruling classes are failing to do this. In 2015 the world’s governments agreed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees or “well below” 2 degrees, while upholding the principle of equity. To achieve this goal, high-income countries, which have extremely high per capita emissions, must achieve extremely rapid decarbonization.

This is not occurring. In fact, at existing rates, even the best-performing high-income countries will take on average more than 200 years to bring emissions to zero, burning their fair-shares of the Paris-compliant carbon budget many times over. Dealing with the climate crisis is not complicated. We know exactly what needs to be done, but we are not doing it. Why? Because of capitalism.

If I wish to get one point across today, it is this: the climate crisis cannot be solved within capitalism, and the sooner we face up to this fact the better. Let me briefly describe what I mean.

The core defining feature of capitalism is that it is fundamentally anti-democratic. Yes, many of us live in democratic political systems, where we get to elect candidates from time to time. But when it comes to the economic system, the system of production, not even the shallowest illusion of democracy is allowed to enter. Production is controlled by capital: large corporations, commercial banks, and the 1% who own the majority of investible assets… they are the ones who determine what to produce and how to use our collective labour and our planet’s resources.

And for capital, the purpose of production is not to meet human needs or achieve social and ecological objectives. Rather, it is to maximize and accumulate profit. That is the overriding objective. So we get perverse patterns of investment: massive investment in producing things like fossil fuels, SUVs, fast fashion, industrial beef, cruise ships and weapons, because these things are highly profitable to capital… but we get chronic underinvestment in necessary things like renewable energy, public transit and regenerative agriculture, because these are much less profitable to capital or not profitable at all. This is a critically important point to grasp. In many cases renewables are cheaper than fossil fuels! But they have much lower profit margins, because they are less conducive to monopoly power. So investment keeps flowing to fossil fuels, even while the world burns.

Relying on capital to deliver an energy transition is a dangerously bad strategy. The only way to deal with this crisis is with public planning. On the one hand, we need massive public investment in renewable energy, public transit and other decarbonization strategies. And this should not just be about derisking private capital – it should be about public production of public goods. To do this, simply issue the national currency to mobilize the productive forces for the necessary objectives, on the basis of need not on the basis of profit.

Now, massive public investment like this could drive inflation if it bumps up against the limits of the national productive capacity. To avoid this problem you need to reduce private demands on the productive forces. First, cut the purchasing power of the rich; and second, introduce credit regulations on commercial banks to limit their investments in ecologically destructive sectors that we want to get rid of anyway: fossil fuels, SUVs, fast fashion, etc.

What this does is it shifts labour and resources away from servicing the interests of capital accumulation and toward achieving socially and ecologically necessary objectives. This is a socialist ecological strategy, and it is the only thing that will save us. Solving the ecological crisis requires achieving democratic control over the means of production. We need to be clear about this fact and begin building now the political movements that are necessary to achieve such a transformation.

Now, it should be obvious to everyone at this point that for the global South, this requires economic sovereignty. You cannot do ecological planning if you do not have sovereign control over your national productive forces! Struggle for national economic liberation is the precondition for ecological transition, and it can be achieved with the steps that my colleagues Ndongo and Fadhel have outlined: industrial policy, regional planning, and progressive delinking from the imperial core.

So that is the horizon. But at the same time we must advance our multilateral bargaining positions. This is what we need to do:

First, we need to push for universal adoption of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. This treaty overcomes the major limitation of the Paris Agreement in that it focuses squarely on the objective of scaling down the fossil fuel industry on a binding annual schedule. The objective here is to do this in a fair and just way: rich countries must lead with rapid reductions, global South countries must be guaranteed access to sufficient energy for development, and those that are dependent on fossil fuel exports for foreign currency must be provided with a safe offramp that prevents any economic instability.

Second, global South negotiators must collaborate to demand much faster decarbonization in the global North, consistent with their fair-shares of the remaining carbon budget.

Third, we must demand substantial resource transfers to the global South. Because the global North has devoured most of the carbon budget, it owes compensation to the global South for the additional mitigation costs that this imposes on them. Our research shows that this is set to be $192 trillion between now and 2050, or about 6.4 trillion dollars per year. Conveniently, this amount can be provided by a 3.5% yearly wealth tax targeting the richest 10% in the global North.

Of course, we should be clear about the fact that Western governments will not do any of this voluntarily. And it is not reasonable for us to place our hope in the goodwill of states that have never cared about the interests of the South or the welfare of its people.

The alternative is for global South governments to unite and collectively leverage the specific forms of power that they have in the world system. Western economies are totally dependent on production in the South. In fact, around 50% of all materials consumed in the global North are net-appropriated from the South. This is a travesty of justice but it is also a crucial point of leverage. Global South governments can and should form cartels to force the imperialist states to take more radical action toward decarbonization and climate justice.

And, by the way, speaking of South-South solidarity, global South governments should negotiate access to renewable energy technologies by establishing swap lines with China so that these can be obtained outside of the imperialist currencies, and thus limit their exposure to unequal exchange.

Comrades. We stand at a fork in the road. We can stick with the status quo and watch helplessly as our world burns… or we can unite and set a new course for human history. The Southern struggle for liberation is the true agent of world-historical transformation. The world is waiting. This is the generation. Now is the moment. Hasta la victoria siempre.

* * *

More on the Congress

The 50th Anniversary Congress on the New International Economic Order adopted a “roadmap for a Global South insurgency to remake the world system.” (For a full list of participants, please click here.)

The assembled delegates debated strategies and tactics for winning a New International Economic Order and worked on major, structural reform proposals under five themes:

• Finance, Debt, and the International Monetary System

• Science, Technology, and Innovation

• Climate, Energy, and Natural Resources

• Commodities, Industry, and International Trade

• Governance, Multilateralism, and International Law

Proposals included a debtors club, cartels for critical minerals, coordination on commodity prices, BRICS financing for Southern state capacity, detailed programmes of regional integration including industrial strategy and collective public purchasing for medicines and components, reduction of material-technical dependency on the Global North, regaining national control over foreign exchange earnings, national and regional industrial policy, investment in food and renewable energy sovereignty, a global global, multilayered buffer stock system for essential commodities including food and critical minerals, coordinated exit from ICSID (International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes), denunciation of bilateral investment treaties, cross-border payment systems where international reserves are deposited, mobilisation of Special Drawing Rights for Southern development, establishing an association of raw material exporters, activate force majeure clauses so that all patents to combat climate change are ended, reparations for historical CO2 emissions from the Global North, and many more.

These proposals will be developed into a renewed and detailed Program of Action overseen by a technical committee of the Progressive International, and will be carried out through online fora and at further in-person conferences, with Algeria, Honduras, Mexico and Colombia all mooted as host nations.

The conference concluded with a presentation by President Miguel Diaz-Canel Bermúdez outlining the vision of the Cuban Presidency of the Group of 77 + China for the New International Economic Order.

See also: Proposals for Unilateral Decolonization and Economic Sovereignty, by Ndongo Samba Sylla (with Jason Hickel)

Not having to negotiate power, taking it for granted that it will not be disputed, leads politically to a harmful attitude that assumes any hint of social pressure is unacceptable. When it occurs, the consequent reaction shows absolute ineptitude shielded with recklessness.

Not having to negotiate power, taking it for granted that it will not be disputed, leads politically to a harmful attitude that assumes any hint of social pressure is unacceptable. When it occurs, the consequent reaction shows absolute ineptitude shielded with recklessness.